Via bloomberg.com

If Hoyos Corp. has its way, the world will soon resemble a Tom Cruise movie.

A closely held company based in Puerto Rico, Hoyos makes devices that photograph human irises for identification purposes, like the technology featured in the films ?Mission: Impossible? and ?Minority Report.?

In the movies, the technology protects super-secret labs and high-security vaults, helps chase down criminals and flashes personalized ads. In the real world, it screens employees of Bank of America Corp. and travelers at London?s Heathrow Airport and helps New York City police track prisoners.

As key patents expire and costs fall, Hoyos wants to make the technology ubiquitous, installing it on mobile phones to verify online payments and cash machines to replace bank cards that require personal identification numbers, said Chief Development Officer Jeff Carter.

?The cost of the devices has come down and the fraud is going up at such an escalating rate that it?s beginning to make sense,? Carter said in an interview at the New York offices of Hoyos, formerly known as Global Rainmakers Inc. Civil libertarians warn that the technology?s use may come with complications for privacy, and increased reliance on it may heighten the risk of misidentification.

Physical Characteristics

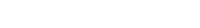

Biometric technology such as iris recognition uses physical characteristics including facial shape, fingerprints, retinal photos and iris patterns to confirm identities.

The technology works by photographing the iris, the colored membrane that controls how much light reaches the retina, and converting the picture into a computer code. The code is compared with one in a database.

Its history goes back to 1936, when Frank Burch, an ophthalmologist in St. Paul, Minnesota, proposed identifying people using the furrows, ridges, rings and freckling that make every iris unique.

It wasn?t until 1987 that two other eye doctors, Leonard Flom and Aran Safir, were granted a patent for the concept of the identification technology.

Flom approached John Daugman, a Cambridge University professor, to develop a way to automate iris identification. Daugman was awarded a patent in 1994, and the first commercial products became available the next year.

The patent covering the basic concept of iris recognition expired in 2005, opening the door for companies to develop their own technology. The 1994 patent will expire this year, according to the website of the National Science and Technology Council.

?Rapidly Evolving?

Iris-recognition is ?rapidly evolving,? said Patrick Grother, a computer scientist at the National Institute of Standards and Technology. The U.S. Commerce Department research unit is developing standards for the process.

Iris-recognition is ?rapidly evolving,? said Patrick Grother, a computer scientist at the National Institute of Standards and Technology. The U.S. Commerce Department research unit is developing standards for the process.

The public acceptance of biometrics in daily life will rise along with global security concerns, with sales poised to jump to $10.9 billion in 2017 from $3.6 billion last year, according to Acuity Market Intelligence, a research consulting firm based in Millburn, New Jersey, that focuses on the technology.

Iris technology is forecast to have a 19 percent share of the global biometrics market in 2017, up from 8 percent in 2009, with revenue rising to $2.l billion from $206.3 million, according to Acuity. The market share for the leading biometric — automated fingerprint identification systems — will drop to 27 percent from 39 percent, the company said.

Prices will drop and the technology will improve in the next decade, said Acuity?s principal, Maxine Most.

Early iris-recognition required subjects to stand close to the camera. Newer devices cost less and can capture an image of an iris from farther away and compare it to a database within seconds.

?They?re doing it at a distance,? Most said. ?They?re doing it on the move.?

Sells For $75,000

SRI International?s Iris on the Move system can capture an image of an iris from as much as 10 feet and can process as many as 30 people a minute, said Mark Clifton, a company vice president. It sells for about $75,000, he said.

Future devices might read irises from more than 30 feet, said Tim Meyerhoff, North American business development director for Iris ID Systems Inc., a company in the recognition business spun off from South Korea?s LG Electronics Inc. in 2009.

In five years, the technology will be widely used for airport security, border control and access control, said Neelima Sagar, an analyst at Frost & Sullivan, a research firm based in Mountain View, California.

Daugman Patent

The Daugman patent is owned by L-1 Identity Solutions, based in Stamford, Connecticut, which was partly sold in September to Safran SA, a French maker of aerospace engines and equipment, for $1.6 billion.

L-1 doesn?t discuss the technology, Doni Fordyce, a spokeswoman, said in an e-mail.

About 20 companies worldwide are working on iris- recognition technology, and the expiration of the Daugman patent ?will have an additional effect,? said Acuity?s Most.

Besides L-1, they include Iris ID, based in Cranbury, New Jersey; Sarnoff Corp., the Princeton, New Jersey-based research company founded as RCA Labs that was integrated earlier this year into SRI International, a nonprofit research institute founded at Stanford University; and Cogent Inc., based in Pasadena, California, which was purchased in December by 3M Corp. for $943 million.

Use Outside U.S.

Iris recognition has caught on faster outside of the U.S. than in it. The United Arab Emirates uses it at border crossings, and among airports besides Heathrow, it?s deployed at Schiphol Airport in Amsterdam. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees uses the technology to verify the identities of Afghan refugees returning from Pakistan.

Inside the U.S., iris recognition is used mostly for secure access to corporate and government facilities.

Bank of America is testing iris recognition at its headquarters in Charlotte, North Carolina, said Laura Hunter, a spokeswoman who declined to comment on plans for its future use.

The New York Police Department in November started photographing irises after two prisoners posed as people facing lesser charges and were freed as a result, said Paul Browne, an NYPD spokesman.

After being fingerprinted and photographed at booking, city prisoners now have their irises photographed by a camera attached to a laptop computer, Browne said in an e-mail.

Before the suspect goes to court for arraignment, the iris is photographed again and compared with the stored image, all of which takes less than 10 seconds, compared with 90 seconds for fingerprint matching, he said.

Federal Government

The U.S. Homeland Security Department in October tested commercially available iris devices at a Border Patrol station in McAllen, Texas.

?We have no specific plans for acquiring or deploying this type of technology at this point,? Amy Kudwa, a department spokeswoman, said by e-mail. She declined to reveal the test results.

Some early users of the technology have moved on, such as the Plumsted Township School District in New Jersey.

In 2003, it became the first U.S. school district to install iris recognition to screen employees and parents. In 2010, it switched to a system using ID cards.

Behind the decision were the technology?s costs, reliability, vulnerability to vandalism and the time it took to enroll people in the system, technology coordinator Thomas Mille said in an e-mail.

Legal Concerns

Iris-recognition technology in the U.S. has raised legal concerns, said Jeffrey D. Neuburger, a partner with the law firm Proskauer Rose LLP in New York who advises companies on technology-related issues.

?Privacy is obviously huge,? Neuburger said in a telephone interview. ?There?s also liability issues associated with the improper use of biometrics or the inaccurate use of biometrics, like if somebody gets identified as somebody they?re really not because of a failure of technology.?

Electronic data can go ?all over the world in seconds,? said Donna Lieberman, executive director of the New York Civil Liberties Union, state affiliate of the American Civil Liberties Union.

?When your iris scan is suddenly doctored or in the wrong hands, the price you?ve paid becomes apparent,? Lieberman said in a telephone interview. ?It?s a little creepy to enter into an era of digital identification that has such a massive absence of privacy protections.?

?Surveillance Society?

Biometrics that ?can be used without the knowledge, participation or consent of the subject risk becoming key tools in a surveillance society where our every movement is tracked and recorded,? Jay Stanley of the ACLU?s Speech, Privacy and Technology project said in an e-mail message.

The database for a national biometric-based identification system would be ?irresistible to identify thieves, hackers and those who want to misuse personal information for crimes like stalking,? the organization said last April in a letter to Congress and the White House.

Hoyos, working to spread the technology, plans to introduce a hand-held device this year providing iris-enabled access to devices such as personal computers.

?You really can?t control technology,? the company?s founder and chief executive officer, Hector Hoyos, said in an interview in New York. ?Oppenheimer and Einstein said it. The cat?s out of the bag. You can try to put certain protocols in place and hope that people who get their hands on technology abide by your protocols. That?s all you can do.?