Via Lew Rockwell, by Mark Nestmann

Via Lew Rockwell, by Mark Nestmann

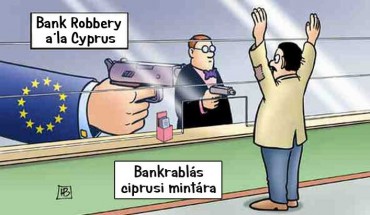

In case you missed the announcement, Cyprus-style bail-ins are coming to a bank near you.

On November 16, leaders of the G20 Group of Nations ? the 20 largest economies ? made an important decision. The world?s megabanks now have official permission to pledge depositor accounts as collateral to make leveraged derivative bets. And if they lose a bet, the counterparty to the contract has first dibs on your money. The governments of these 20 countries are now supposed to put these arrangements into law. Most, including the US, have already done so.

You could be forgiven for not paying much attention to the G20 meeting, because it was mostly ?more of the same? ? the latest plan to have central banks inject trillions more dollars into the global economy.

But the G20 also endorsed a proposal with a mind-numbingly tedious title: Adequacy of Loss-Absorbing Capacity of Global Systemically Important Banks in Resolution. Not exactly a page-turner. Your average American is more likely to watch Chicago Fire than to delve into the minutiae of the global financial system.

But this proposal profoundly changes the rules for banking globally, and not in a good way. Deposits in banks that are ?too big to fail? will be ?promptly recapitalized? with their ?unsecured debt.? This avoids those nasty taxpayer-funded bailouts that proved so politically unpopular during the 2008-2009 financial crisis.

And the largest chunk of unsecured debt is your bank deposits. Insolvent banks will recapitalize themselves by converting your deposits ? checking accounts, but also money market accounts and CDs ? into stock. Thus, when you deposit money in a bank, you?re taking the same risk as someone buying a stock. Or, for that matter, betting on a horse named ?Falling Star? at the local racetrack. Because, in effect, that?s what banks are doing with your money.

The G20 has also officially declared that derivatives ? the toxic contracts Warren Buffett calls ?financial weapons of mass destruction? ? are secured debts. Since your bank deposits are now only unsecured debt that the bank has pledged to a secured creditor, guess who gets your money if the bet goes the wrong way for the bank? Answer: It?s not you.

Heads, the bank wins. Tails, you lose.

Fortunately, ?insured deposits? won?t be subject to this treatment. In the US, 100% of deposits in insured banks are protected up to $250,000 per depositor, courtesy of federal deposit insurance. But it?s hardly reassuring that this fund has a reserve ratio under 1%. For every $100 on deposit, the FDIC has less than one dollar to back it with.

This is still a lot of money ? $54 billion at the end of September. But it?s dwarfed by $6 trillion in insured deposits, not to mention derivatives contracts with a total value of nearly $300 trillion. Indeed, the failure of just a single major Wall Street bank could exhaust the fund.

Federal law authorizes borrowing from the US Treasury to make up the shortfall, but when a banking crisis hits, it?s not likely to occur in a vacuum, as I described in this essay. Lots of other people will be demanding a handout, many of them with stronger political connections than you or I could ever hope to muster.

How bad could it get? Well, under the scenario the G20 just blessed, uninsured bank depositors would be even worse off than account-holders in the government-owned banks in Cyprus that became insolvent in 2013. Their claims were considered superior to those of derivative counterparties. Some uninsured depositors got almost half of their money back (although at one government-owned bank, they got nothing).

How bad could it get? Well, under the scenario the G20 just blessed, uninsured bank depositors would be even worse off than account-holders in the government-owned banks in Cyprus that became insolvent in 2013. Their claims were considered superior to those of derivative counterparties. Some uninsured depositors got almost half of their money back (although at one government-owned bank, they got nothing).

A more apt example would be Lehman Brothers. When it declared bankruptcy in 2008, unsecured creditors got about 21 cents on the dollar. You might be wondering why the G20 made this decision. The obvious incentive is to avoid politically unpopular bailouts of megabanks that are ?too big to fail.?

But there?s a less obvious reason as well. The G20 hopes that you?ll invest in government bonds backed by the ?full faith and credit? of its member governments. That will have the effect of keeping down interest rates on the alarmingly high debt carried by almost every G20 member.

How can you protect yourself?

The most important precaution is to minimize your exposure to the banking system. Keep bank deposits well below the deposit insurance maximums. Accumulate physical currency, precious metals, and other ?real assets.?Diversifying your investments internationally also makes sense, but because bail-ins have now gone global, it?s no longer as simple as just opening an account outside the US or whatever other country you live in. Use only strong, well-capitalized banks to hold the funds you keep in the banking system. Look for banks with as high a level of ?Tier 1? liquidity as possible ? 25% at the minimum. (By comparison, the minimum required in the US is only 6% to be classified as ?Well-Capitalized.?) If you have at least $500,000 or so to spare, open an account with an offshore private bank that has no commercial lending or derivatives exposure.

I don?t know when the next global financial crisis will hit. But when it does, I do know who will pay for it. And it won?t be the bankers or the financial geniuses who designed the ?financial weapons of mass destruction? that led to their downfall.

Get your assets out of the ?too big to fail? banks ? now. It?s only a matter of time before the SHTF.